Is the development and use of AI in the provision of medical care legal?

The use of AI and new technologies in the health sector raises new questions related to the collection and use of vast quantities of personal data. In Helse Bergen's sandbox project, we have explored what leeway exists for the use of personal data in a clinical decision-support tool based on AI.

General requirements for legal basis

The EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) states that the processing of personal data shall be lawful only if and to the extent that at least one of the legal bases set out in Article 6(1)(a to f) applies.

What constitutes the processing of personal data?

In short, personal data can be defined as any information that can be linked to a natural person, directly or indirectly. It does not matter what format the information is in. Text, images, video and audio are all included. The term “processing” covers everything done with respect to the data. This includes collection, structuring, amendment and analysis.

Article 9(1) establishes a general prohibition against the processing of particular categories of personal data. This includes health data, because this type of personal data is considered to be of a particularly sensitive nature. Article 9(2) lists a number of exceptions to this prohibition. The exceptions listed in this provision are exhaustive.

Supplementary legal basis and principle of legality

In some cases, Article 6 (3) and Article 9(2) of the GDPR require a supplementary legal basis in member state law. This means that the data controller must be able to demonstrate that the processing of the personal data concerned has a legal basis in both the GDPR and in national law.

Data controller

The term “data controller” is used in health-related legislation to denominate the person deemed to be the controller pursuant to the GDPR. According to Article 4(7) of the GDPR: “‘controller’ means the natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body which, alone or jointly with others, determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data”.

One question is how clear the supplementary legal basis has to be. Article 6(3) may provide some guidance when the legislator is framing such a legal basis. The provision establishes that a specific statutory provision is not required for each and every processing situation as long as the purpose of the processing is laid down by national law, or the purpose is necessary for the exercise of official authority. As we shall see more clearly in the following, both Article 6(1)(c) and (e) will be relevant legal bases for the development and use of Helse Bergen's algorithm.

According to the Norwegian Data Protection Act’s preparatory works, processing on the basis of Article 6(1)(c) of the GDPR must have a supplementary legal basis in which its purpose is specified. However, it is sufficient that the supplementary legal basis imposes a legal obligation on the data controller, the fulfilment of which requires the processing of personal data.

See Prop. 56 LS (2017-2018) pt. 6.3.2 at www.regjeringen.no (pdf) (in Norwegian)

For Article 6(1)(e) of the GDPR, it is sufficient that the data controller needs to process the personal data for the exercise of that authority which follows from the supplementary legal basis. Thus, the supplementary legal basis does not need to expressly regulate the specific processing of personal data.

Is there a legal basis for the use of personal data for the development and use of AI in clinical practice?

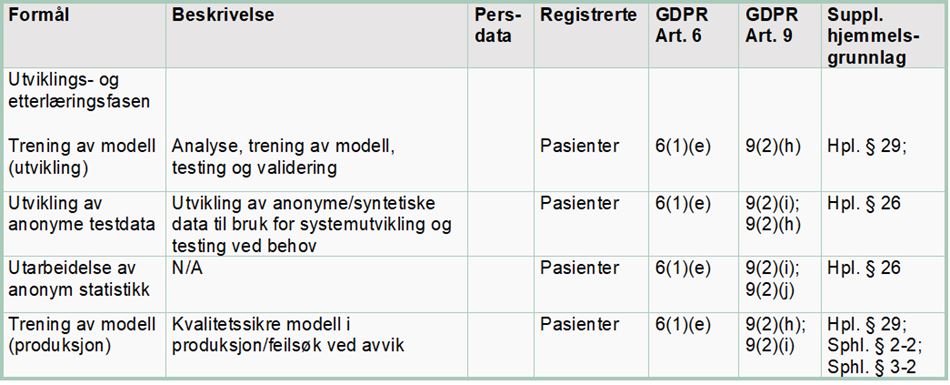

For the purposes of the following presentation, it is natural to address the question of legal basis in relation to the algorithm model's two main phases: (1) the development and continuous machine learning phase, and (2) the application phase, in which the algorithm model is used in clinical practice.

(1) Legal basis for the development and continuous machine learning phase

The algorithm has been developed on the basis of historic health data from almost 200,000 patients treated by Helse Bergen in the period from 2018 to 2021. This means that the health data collected about one patient is used for the purpose of providing medical assistance to others in addition to the specific patient concerned. During the continuous machine learning phase, new health data are continuously fed into the algorithm, so that it is always updated and develops in line with any changes that arise. The processing of health data in the development and continuous machine learning phase requires a legal basis in the GDPR and national law.

Article 6(1)(e) of the GDPR establishes a requirement that the processing is “necessary” for the performance of a “task carried out in the public interest” or in the “exercise of official authority vested in the controller”. The purpose of developing the algorithm is to reduce the number of readmissions, improve patient follow-up and use health sector resources more efficiently.

Article 9(2)(h) may apply when the processing of personal data is “necessary” for the purpose of “preventive or occupational medicine” or for the “provision of health or social care or treatment or the management of health or social care systems”. Article 9(2)(i) may also be used for the processing of health data when it is “necessary for reasons of public interest in the area of public health”. The term “public interest” is not defined in any more detail. It is, however, exemplified in terms of “ensuring high standards of quality and safety of health care and of medicinal products or medical devices”. It may be natural to use Article 9(2)(i) in connection with internal quality assurance on the model during its application (the continuous machine learning phase).

Article 6(3) and Article 9(2)(h) and (i) establish that the processing of health data must also have a supplementary legal basis in national law.

Supplementary legal basis in healthcare legislation

The starting point for all processing of health data by the health service is that healthcare personnel are subject to a duty of professional secrecy, cf. Section 21 of the Health Personnel Act and Section 15 of the Medical Records Act. The duty of professional secrecy is intended to protect the patient’s fundamental right to privacy and maintain public confidence in the health service. All exemptions from the duty of professional secrecy require the patient’s consent or that the exemption is warranted in law.

A typical and practical exemption from the duty of professional secrecy is the sharing of information with other healthcare personnel when it is “necessary” to provide “adequate medical assistance”, cf. Section 25 and Section 45 of the Health Personnel Act. A corresponding legal basis is required to use one patient’s health data to develop an algorithm that is intended to be used to provide medical assistance to other patients. Since it is not particularly practical to ask every single patient for their consent to waive the duty of professional secrecy, any such secondary use of health data must be covered by a statutory exemption from that duty.

Section 29 of the Health Personnel Act, which entered into force in the summer of 2021, permits the duty of professional secrecy to be waived in order for information from patients’ medical records and other treatment-oriented health registries to be made accessible. Under particular conditions, and upon application, the provision may be used as a legal basis for the development and continuous machine learning of AI-based decision-support tools, cf. Section 29(1)(a) of the Health Personnel Act.

Section 29 of the Health Personnel Act

“The Ministry may, upon application, determine that the duty of confidentiality pursuant to Section 21 shall not prevent information from patients’ medical records and other treatment-oriented health registries being made available when

a.) the information shall be used for an expressly specified purpose related to statistics, health analyses, research, the development and use of clinical decision-support tools, quality improvements, planning, management or emergency preparedness to promote health, prevent disease and injury or provide better medical and social care services.”

(our emphasis)

In the Act’s preparatory works, the Ministry of Health and Social Care stated that:

“A specific assessment must be made in which the benefits to society must be weighed against the infringement of the individual’s privacy. Considerations relating to the duty of professional secrecy and the patient’s right to protection from the spread of [personal] information shall weigh heavily.”

See Prop. 63 L (2019-2020), Chapter 16.1, page 129 (pdf) (in Norwegian)

To ensure that the underlying data are always representative, the model must be constantly supplied with new health data. Such continuous machine learning may be authorised pursuant to Section 29 of the Health Personnel Act, cf. the word “development”.

When processing health data for internal control and quality assurance, it is natural to use Section 26 of the Health Personnel Act as the legal basis and exemption from the duty of professional secrecy. In this context, quality improvement is understood to mean verification that the algorithm’s use in clinical practice is fair and reasonable.

The introduction of Section 29 of the Health Personnel Act in the summer of 2021 may be seen as a signal that the authorities wish to facilitate increased use of AI in clinical practice. The Norwegian Directorate of Health is the relevant authority for adjudicating applications for dispensation.

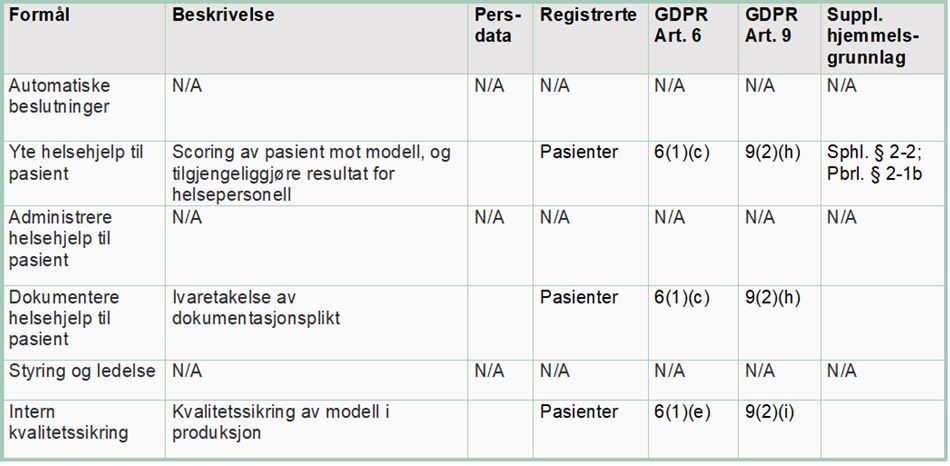

(2) Legal basis in the AI-application phase

In this phase, the decision-support tool is used as part of the health service’s clinical practice. The term “clinical” implies that the purpose of the tool being developed is to provide practical medical assistance. The algorithm will analyse the individual patient’s data and score the patient’s likelihood of being readmitted in the future. A software robot will then cut the score generated by the algorithm and paste it into the patient’s notes in the medical records system DIPS, where it will be visible to the treating physician.

By using the individual patient’s health data, the algorithm will predict the risk of the patient being readmitted to hospital in the future. Health trusts have a duty to provide adequate health and social care services, and must therefore process the data deemed necessary and relevant to provide such services. For this processing of personal data, it is relevant to examine Article 6(1)(c) of the GDPR in further detail. This provision requires that

“[…] processing is necessary for compliance with a legal obligation to which the controller is subject”.

Because the decision-support system processes patient health data, one of the exemptions laid down in Article 9(2) must be applicable for the processing to be lawful. Article 9(2)(h) establishes a right to process health data if the processing is “necessary” in connection with “preventive or occupational medicine” or “the provision of health or social care or treatment”.

A supplementary legal basis may be found in Section 2-2 of the Norwegian Specialist Health Services Act, cf. Section 2-1, which requires the specialist health service to provide adequate health services to citizens:

“The health services offered or provided under this Act must be adequate. The specialist health service shall organise its services such that the personnel who perform the services are able to comply with their statutory duties, and such that the individual patient or user is provided with a holistic and coordinated suite of services.”

The duty to provide an adequate service is a legal standard in healthcare legislation. A legal standard is dynamic and will develop in line with developments in society and new standards for medical assistance. This creates a higher degree of unpredictability for the patient. However, access to and the processing of personal data are a prerequisite for and a natural part of, the duty to provide adequate medical assistance. According to the Health Personnel Act’s preparatory works, when the requirement for providing adequate services is discussed, the substance of the duty to provide adequate services must be assessed on the basis of legitimate expectations, the health personnel's qualifications, the nature of the work and the situation in general.

See Section 4.2.5.3 of Proposition no 13 to the Odelsting (1998-99) at www.regjeringen.no (in Norwegian)

The duty of health personnel to provide an adequate service applies irrespective of the patient's voluntary will or capacity to exercise their own autonomy. The requirement to provide adequate care may be understood as a duty to develop and offer health services based on new knowledge and technologies, including the use of AI where this is expected to be beneficial.

Section 39 of the Health Personnel Act establishes that the person providing medical assistance has a duty to document the care provided. This duty implies an individual duty to record information about the patient and the medical assistance provided, which is relevant and necessary, see also Section 40 of the Medical Records Act and the Medical Records Regulations. The duty of documentation is grounded in the duty to provide adequate care.

A specific legal basis must exist if data are to be processed over and above that which is deemed necessary and relevant for the provision of medical and social care services and the health personnel’s duty to document the same in the specific case concerned.

Furthermore, Section 19 of the Medical Records Act establishes that healthcare providers have a duty to:

“… ensure that relevant and necessary health data are available for healthcare personnel and other cooperating personnel when this is necessary to provide, administer or verify the quality of the medical assistance provided to the individual.”

This provision may be used as a legal basis as long as the processing of the data is necessary and relevant for the provision of the service.

The right and duty to share patient data with cooperating personnel is also laid down in Section 25 and Section 45 of the Health Personnel Act.

In summary, there are several provisions in the legislation regulating the provision of health services that permit personal data to be used for patient care (particularly Section 2-2 of the Specialist Health Service Act and Section 19 of the Medical Records Act). A fundamental precondition for health personnel being able to provide adequate medical assistance (cf. Section 2-2 of the Specialist Health Service Act) is access to relevant and necessary patient data.

Prohibition against automated decision-making vs. decision-support systems

Article 22 of the GDPR prohibits decisions based solely on automated data processing. For such a prohibition to be applicable, the decision must be made without human intervention. In addition, the decision must produce legal effects concerning the data subject or have a similarly significant impact on them. The requirement for human intervention implies that the decision-making process must include an element of real and actual assessment performed by a human being.

The algorithm model in Helse Bergen's project is limited to being decision-support tool, which will only be used as a guide to health personnel in their assessment of patient follow up. The Health Personnel Act’s preparatory works make it clear that the term “decision-support tool” shall be broadly understood and that it encompasses all types of knowledge-based aids and support systems, which may provide advice and support, and may guide healthcare personnel in the provision of medical assistance. This includes the development and use of systems built on artificial numerical analysis and systems built on machine learning. The algorithm’s recommendation will thus form only one of many factors that determine the measures to be implemented.

It must nevertheless be emphasised that use of the algorithm in clinical practice is based on a profiling of the patient, cf. Article 4(4) of the GDPR. Profiling is defined as “any form of automated processing of personal data consisting of the use of personal data to evaluate certain personal aspects relating to a natural person, in particular to analyse or predict aspects concerning that natural person's performance at work, economic situation, health, personal preferences, interests, reliability, behaviour, location or movements”. Even though profiling alone does not trigger the prohibition laid down in Article 22, profiling may indicate that there is a high risk associated with such processing. This is particularly true of profiling that incorporates health data.

Although the algorithm is used as a decision-support system, there is a risk that healthcare personnel may rely wholly on the algorithm’s result, without performing any independent assessment of their own. In that case, use of the AI tool will, in practice, be fully automated. Measures to reduce the risk of this occurring include ensuring that healthcare personnel receive sufficient information and training before use of the tool is adopted, presenting the results in terms of probable outcomes rather than categorical outcomes, being transparent with regard to the algorithm’s accuracy and introducing procedures and control mechanisms to uncover errors in the model.